Our Approach

Applying implementation science for system improvement

PSSP works with communities, service providers and other partners across Ontario to create sustainable, system-level change. Part of what we do is help identify evidence-informed programs and practices that work. Alongside this, we support effective implementation – without this, the benefits of good programs are left unrealized.

We draw from implementation science, a large body of scientific evidence that aims to uncover effective implementation strategies. By using this evidence-informed approach to implementation, we can support change efforts across the province and ultimately, improve our mental health and addictions system.

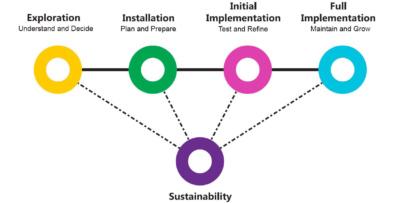

At PSSP, our implementation process is informed by the Active Implementation Frameworks developed by the National Implementation Research Network (NIRN). The process typically includes four distinct stages. Organizing our work into phases helps ensure comprehensive planning, provides time to engage the right people, allow us to attend to key drivers for successful implementation, and iteratively refine new initiatives until they work well.

You

can read more on what

happens in each implementation stage here. For more information

on Implementation Science, visit the National Implementation

Research Network's (NIRN) website.

In addition to this guiding framework, the tools below and guiding principles are informing the work of PSSP.

Our Focus on Implementation

Implementation is a set of activities meant to bridge the gap between what is known and what is done. In simple terms, it is a rigorous, scientific step-by-step process for turning knowledge into new practices. Evidence-informed approaches are necessary in the mental health and addictions system for effective promotion, prevention, and early intervention, but they may be insufficient without consideration for the implementation process and a deep understanding of the context in which approaches are being implemented.

Exploration

Using an implementation-sensitive approach, (see diagram) means starting with an ‘Exploration’ of the current situation and challenges within a particular system, setting or community, before moving through a series of active implementation stages. It is at this early stage that an evidence-informed intervention is first identified. . This stage helps teams to better understand the current context or situation within a local system and then decide which evidence-informed intervention is best suited to the needs of that system. It also helps them to decide which intervention has the best opportunity for advancing successful approaches.

Installation

Following the selection of an intervention, the group moves into the ‘Installation’ stage which involves planning for the identified intervention. Determining the core components of the intervention and preparing for how they will be implemented in the local context is a critical step of the Installation stage and in the overall Implementation process.

Initial Implementation

As the group moves into the Initial Implementation stage, it is important to understand that striving to implement interventions faithful to their original intentions (maintaining fidelity) is desirable, however, it is important to adapt activities to specific situations and the needs of local communities, which ensures that the intervention remains relevant and meaningful.

Initial Implementation allows an intervention to be tested on a smaller scale to help identify necessary tweaks or local adjustments. Through continuous refinement and quality improvement during the Initial Implementation stage, the goals of relevancy and meaningfulness can be most effectively achieved.

Full Implementation

‘Full Implementation’ – the final stage – is reached only when the intervention is a cohesive and integrated feature of the local system. At this stage, our aim or goal is to achieve full sustainability of the intervention over the long term. To achieve this, it is important to consider and build in this goal during the implementation process. This is best achieved by assessing the readiness of communities to implement, and developing readiness where needed, from the onset of an implementation process.

An implementation-sensitive approach also includes developing an Implementation Plan that takes into account the capacity (the skills, knowledge and availability) of the workforce, the environment, and processes at the organizational and system levels, and the leadership required to create and maintain system improvements over time. Building in mechanisms for assessing and supporting readiness also play an important role in the overall and long-term sustainability of the system change.

Quality Improvement Tools

Quality improvement (QI) tools provide a formal approach to improving processes of care, recognizing that in order to positively change system outcomes, we must also systematically improve system processes. By focusing on the analysis of a system’s performance, application of QI tools (e.g. process mapping, Plan-Do-Study-Act [PDSA] cycles) can result in increased efficiency and improved performance on many levels. PSSP has incorporated several QI approaches and tools in our system improvement approach to support the implementation of evidence-informed interventions.

Use of Evidence

PSSP acknowledges that successful outcomes require a combination of proven interventions and effective implementation techniques. There are many definitions of evidence-based practice; these are largely dependent on varying levels of scientific rigour. We recognize that many forms of knowledge, taken together, make up evidence. These forms include research, professional expertise, the lived experience of people and families, and cultural and traditional knowledge. We also recognize that the use of evidence must take into account the local context.

Health Equity

Health inequities are avoidable, unfair, and systemic differences in health outcomes and access to care between and among population groups. Health inequities have roots in factors that lie outside of the health system, such as the conditions in which people live, work and grow – also known as the social determinants of health. Here are a few examples of health inequities:

- Low income Canadians report significantly poorer mental health.

- 43% of transgender people in Ontario have attempted suicide, compared to 3.5% in the general population.

- Immigrant, refugee and racialized groups in Canada face barriers in accessing mental health services, such as gaps in language interpretation services and lack of culturally appropriate services.

A health equity approach aims to level the field by reducing or eliminating differences in health outcomes for marginalized populations in order to achieve health for all.

PSSP is supporting local systems to improve coordination of and enhance access to mental health and addictions services for marginalized populations in Ontario by integrating a health equity approach. We work to access and integrate the expertise of lived experience and the voices, priorities, and perspectives of minority, marginalized, and vulnerable populations. The use of evidence, data, and validated tools also ensures health equity is a primary driver of our system change work. We use the Health Equity Impact Assessment (HEIA) tool to better understand the equity impacts of our interventions in order to maximize positive outcomes for marginalized populations.

Developmental and Ongoing Evaluation

PSSP's evaluation methods include traditional logic models, performance measurement and also qualitative methods (e.g. case studies). We use developmental evaluation to guide the implementation of interventions within complex environments. Developmental evaluation is often used in response to complex issues that involve multiple stakeholders and large-scale change across systems. This complexity requires flexible evaluation methods and ‘agile’ evaluators who are able to respond to unexpected situations that will arise when innovations are implemented in dynamic systems.